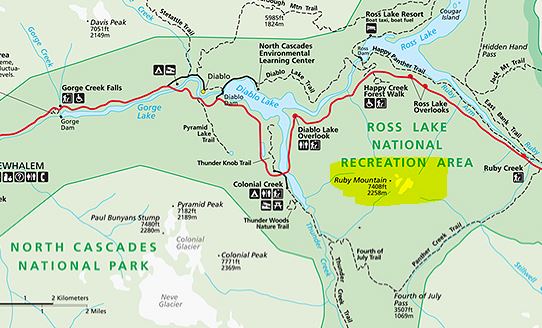

Consider Ruby Mountain. It’s not particularly tall. At about 7,400 feet, it’s one of hundreds of similar peaks in the North Cascades, and it doesn’t make the list of the 100 tallest mountains in Washington. As a piece of recreational real estate, though, it’s hard to beat. Water surrounds much of the mountain’s base. Diablo Lake splits into Thunder Arm stretching south and the Narrows to the northwest, embracing the western side of the peak. Ruby Arm, named for the creek that flows into Ross Lake from the east, snakes around the northeast side. It’s a logical place for a road, and the North Cascades Highway curves around the mountain’s flanks, following the waterways and pausing at several scenic overlooks. This is where most visitors stop, grab cameras from their cars, and walk to the edge, snapping views northward up Ross Lake that hint at the vast wilderness of North Cascades National Park’s northern unit.

The thing that makes Ruby Mountain so intriguing is its prominence, a topographic measure of the height from the lowest complete contour line surrounding a peak to the summit. To us non-mountaineers, prominence is useful as an indicator of potential view quality from the summit. Ruby Mountain has about 3,900 feet of “clean prominence,” making it number 21 on the list of Washington’s peaks by prominence. From Ruby’s summit, 360-degree views take in grand sweeps of the North Cascades.

For these reasons — excellent location and high prominence — Ruby Mountain in the 1960s was selected as the site of a tram that would take visitors to its summit, putting the alpine magnificence of the proposed North Cascades National Park within view of anyone willing to make the trip up the mountainside.

Years of debate over whether the National Park Service or the United States Forest Service was better able to manage the North Cascades for its highest use, recreation, eventually came down to a study. The study conditionally recommended a national park, reasoning that access to the North Cascades must “not be limited … to the traditional roads and trails. This area calls for more imaginative and creative treatment,” including trams.

Why a tram? Keep in mind, the study recommended a North Cascades national park largely because a park would attract “large numbers of people who either do not wish, are unable, do not have the time, or cannot afford wilderness-type travel” to see the spectacular mountain scenery. The question was how to get the people to the views. A tram could be camouflaged by the forest, offered a viable substitute for cars, and would accommodate large numbers of visitors.

From its founding in 1916, the Park Service has tried to deal with the inherent paradox of its Organic Act, which requires preserving “unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations” park scenery, wildlife, and historical remnants while also providing for “enjoyment of the same.” In its first decades, the agency focused more on providing access than preserving nature. But growing ecological awareness and soaring visitation in the 1950s and 1960s gave leaders cause to reconsider what providing access could and should look like going forward. A new national park needed to incorporate new thinking about these issues.

In Congressional hearings on the North Cascades park bill in the 1960s, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall and Park Service director George Hartzog, Jr., said the tram idea was the latest in park planning, a feasible alternative to cars that would wreak far less damage on sensitive ecological zones. Scenic roads, the hallmark of the Western national parks, diminished wilderness. “I don’t believe that we can continue to build roads to take care of the people who want to see these parks by automobile,” Hartzog said.

Although many legislators, conservationists, and Park Service rank and file were skeptical, Washington Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson and Representative Lloyd Meeds strongly supported the Ruby Mountain tram proposal, seeing it as vital to attracting visitors to the remote mountain fastness. Why go, after all, if visitors couldn’t see anything when they got there? Providing access was a hallmark of national park management, and in a rugged wilderness like the North Cascades, trams were a logical solution.

By the time the bill creating North Cascades National Park was enacted in October 1968, trams had been part of the discussion for several years. And Ruby Mountain, with its high prominence and proximity to water and the as-yet-incomplete North Cascades Highway, was an ideal location. A Ruby tram could ferry skiers in winter and sightseers in summer.

But the proposal eventually fell victim to two variables, time and money. Time brought new, stricter environmental laws like 1970’s National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which required federal agencies to complete studies showing potential environmental effects of their proposals. Even though Ruby Mountain lies inside the boundaries of Ross Lake National Recreation Area, which has less strict rules than the national park proper, a tram was obviously going to have a significant impact on the environment there. And impact studies added expense. In 1970, the Ruby Mountain tram was projected to cost $8 million. By the end of the decade, when the tram’s most fervent supporter left Congress, the estimated cost had ballooned to $13 million. In the face of an economic downturn and correspondingly stagnant national park funding, the Ruby Mountain tram proposal died.

What this means is that today most visitors have to be content with seeing the North Cascades from overlooks above Diablo and Ross lakes along the scenic highway twining through the park. There is only one way to see the views from atop Ruby Mountain, and that is to hoof it about 4,300 feet up a partially unmaintained trail starting at Fourth of July Pass, itself 2000 feet above Thunder Creek.

I hiked to the remarkably unscenic pass from the Thunder Creek trail in September. A nondescript spot in the middle of a dim forest, the only sign you’ve reached the pass is a pair of knee-high stone cairns. These mark the pass and the beginnings of the primitive trail to Ruby’s summit. A friend who climbed the peak a few days earlier said many downed trees made route-finding quite difficult, but the views from the top were as advertised. I believe him, but it’s not going to get me up there anytime soon.

On the other hand, I have enjoyed a few tram rides on the fringes of national parks and wilderness areas.

We rode the Rendezvous Mountain (built 1966) tram just south of Grand Teton National Park a few years ago, and the Wallowa Lake tram (built 1970) just north of Eagle Cap Wilderness in northeastern Oregon a few years before that. I can appreciate the access that trams provide, though I’m grateful the ones I’ve been on are sited in areas considered park or wilderness gateways and not within the park or wilderness itself.

I’ve been thinking about trams recently, partly because some of the biggest news out of the national parks this year has been about the swarms of visitors to the popular crown jewel parks.

Zion National Park, which saw visitation increase more than 35 percent between 2010 and 2015 and may log more than 4 million visits during this Park Service centennial year, is considering limits on the number of visitors it allows in its most heavily used areas (the park is taking public comment until November 23).

And that’s just one example. Great Smoky Mountains (10.6 million), Grand Canyon (5.5 million), Rocky Mountain (4.1 million), Yellowstone (4 million), Yosemite (4 million), Olympic (3.2 million), and Grand Teton (3.1 million) national parks all set new visitor records in 2015. The trend is expected to continue this year. In North Cascades, by most measures a fairly lightly visited park, rangers told me visitation is up 30 percent from last year.

Clearly, we are going to have to do something to rebalance the access-and-preservation conundrum in the parks. Publicizing lesser-known parks and other types of scenic areas is a worthy strategy, but the fact is, most folks want to see their crown jewel national parks, and it’s those parks that feel the impact of those millions of visits. At the same time, I suspect that people who’ve saved for years to visit the parks will not be happy about waiting in hours-long lines at shuttle stops or entry stations. Goodwill is critical to the parks’ success, and public support keeps federal money flowing to parks (albeit not nearly enough, given the $12 billion maintenance backlog across the national park system).

Trams are probably not a feasible solution to this complicated problem, although canoeing on jewel-toned Diablo Lake and gazing at Ruby Mountain, I could understand the rationale behind the tram proposal there. Moving people around inside our beloved national parks is going to require out-of-the-box thinking and creative action. The selfsame scenic roads that bring people to the parks exacerbate the overuse problem. Reducing the number of vehicles on those roads, through shuttles or sightseeing buses like those used in Yosemite during the summer months, is a step in the right direction, but there’s much more work to be done.

Great write up! We never knew about the tram proposal – but then again, we have yet to visit the North Cascades. Maybe we’ll make out that way this weekend.

Ruby will look different–lots of snow up there now, I hear. Thanks for reading, and have a fun trip!