Like many who love our nation’s public lands, I fear for their future under the next president. Attacks on the sanctity of public lands — federal, state, and municipal lands set aside for the benefit of all citizens — are increasingly common. The Malheur National Wildlife Refuge occupation is perhaps the most prominent, but I’ve been dismayed to learn of recent land sales inside the proposed Bears Ears National Monument in Utah and outside Zion and Bryce Canyon national parks, too.

I believe that giving states control over federal public lands is misguided. It is precisely what those who developed public lands policy were trying to avoid. As we’ve seen at Comb Ridge, privatizing public lands enriches the corporations that purchase them, not the citizens for whom the land was set aside in the first place. The notion of a trickle-down effect in which citizens reap the benefits of selling off their landed heritage is laughable. In many cases, the only people who will profit are the resource company executives who will strip the land of any economic benefit then leave behind a devastated landscape.

We are on the brink of a new era in public lands policy. It’s possible the Department of the Interior could see Sarah “drill, baby, drill” Palin or U.S. Rep. Rob “return it to the states” Bishop as its next Secretary. Make no mistake: we citizens will lose land that has belonged to us for a century or more, and we will see no profits from those losses. The challenge for those of us who love public lands is to do what we can to try to stem the tide in a federal political environment that will favors privatization.

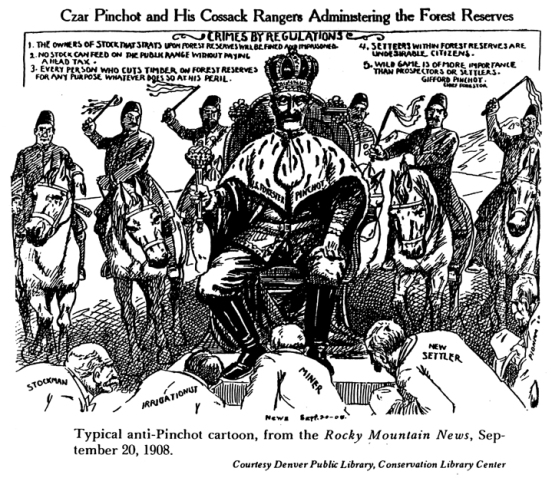

Let’s remember why we set aside public lands in the first place. As historian Char Miller suggests, Gifford Pinchot, first chief of the U.S. Forest Service, should get more credit for developing “the notion that these lands are public, that we own them as a body politic. As a consequence, they don’t belong to Utah, they don’t belong to Florida…[Pinchot] recognized that public lands are democratic, something that all of us are invested in.”

Every public lands agency and every American citizen has benefited from Pinchot’s thinking. By tirelessly advocating for democratic ownership of public lands, he set the stage for lands management in the National Park Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

This is important. Before the first forest reserves were set aside in the 1890s, the federal government spent a lot of time and effort trying to give away as much of the public domain as possible. It wasn’t until the country was settled from coast to coast — when the frontier was declared “closed” in 1890 — that some folks realized our seemingly limitless natural resources were anything but. Pinchot and his ally President Theodore Roosevelt believed we should manage natural resources like timber, water, and grasslands conservatively in order to make them sustainable. In other words, resources should be carefully managed for “the greatest good for the greatest number over the long run.”

Miller points out that Pinchot added the “over the long run” clause to the phrase, originally coined by 18th-century philosopher Jeremy Bentham, and in so doing founded American conservationism. Public lands were to be for the public benefit, a keystone concept of our democracy.

We have benefited enormously from this farsightedness.

For example, the availability of public lands, especially scenic areas, helped create the tourism industry in the United States. No one disputes the economic benefits of tourism.

These lands belong to “we the people” and we have a stake in their management and disposition. That stake includes debates over their management and disposition, part of the messy democratic process that we citizens have a duty to engage in thoughtfully and civilly.

Which brings us to now. I expect President Obama will create a few more national monuments before he leaves office, and then I expect a drought of new designations for several years at a minimum. I also expect some lands we currently own will be sold to the highest bidder, a prospect that would horrify Pinchot, Roosevelt, John Muir, Aldo Leopold, Bob Marshall, Howard Zahniser, Dave Brower, and many others who spent their lives working to protect public lands for the people. They understood that public lands are central to our understanding of ourselves as Americans.

Therefore, I will be devoting more time to public lands preservation, a cause about which I am passionate. I do not expect to change the minds of those who fancy themselves modern sagebrush rebels or those who want to sell it all, but I will look for opportunities to reach out to them and see what we might have in common. I will also be volunteering more on public lands near me, including Mount Rainier National Park, and supporting organizations that work on behalf of public lands. The more people that speak out for public lands, whether by writing letters and checks or doing trail work or speaking at hearings, the better chance we have to preserve our great and imperiled natural heritage. I hope you’ll join me.

Well said! Thank you.

The scariest aspect of a Trump presidency for me is precisely what you’ve described, as well as changes to environmental protections and regulations. Hard to believe we’ve come this far only to be derailed with this election…